Poems by Esme Sammons Positive Spin

Positive Spin

“

His sense of humor and positive outlook make him a favorite on the amputee ward.”—VFW Magazine, “Wounded Vets Rebound”

The clock is broken and marks eternal 3 o’clock.

Her hand rests on his arm, pale against the tan;

Her face an oval cut from paper.

He sleeps for now.

If she speaks, her lips will surely shatter—

Like cheap pottery—

And anyway,

What will she say?

His chest moves with tidal breath,

Rising and falling like coastal waves.

Under the blanket,

Ridges of his legs stretch uneven—

Diminished.

Later she will weep as she folds the laundry

And finds his single sock.

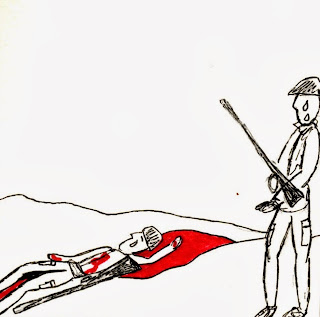

Above is only BlueStrangely quiet after impact

Above is only blue.

Percussive roar now muffled

comes from an unimportant distance

--disconnected--

More felt than heard,

Swaddled as if in cotton, it thumps

counter rhythm to the internal beat,

but fades in numbing fingertips.

Crimson seepage spreads a shroud,

consumed by thirsty sand.

Above is only blue.

For in that Sleep--

For in that Sleep--

If I shut my eyes theirs will open in the dark,

silverAgainst the blood red screen of my lids I watch them open—

They can see—

They can smell me here.

I don’t know I don’t know

idon’tknowidon’tknow

Their voices; clogged with roots and clotted earth they—

whisper

Telling of their (that unknown world from which no traveler returns) dreams—

Beckoning, questioning:

Why why why why whyPeace will come at such a price if only I—

I am full of the hum of voices,

Here in the dark—

Mustn’t mustn’t musn’tIf I open my eyes I—

Human elementalWhen broken into its most essential parts, the human body is made of

65% Oxygen

18% Carbon

10% Hydrogen

3% Nitrogen

1.5% Calcium

1% Phosphorous

0.35% Potassium

0.25% Sulfur

0.15% Sodium

0.15% Chlorine

0.05% Magnesium

0.0004% Iron

0.00004% Iodine

And trace amounts of flourine, silicon, manganese—

zinc, copper, aluminum, and arsenic.

Monetarily speaking, the sum of these parts is worth less than a dollar.

But we are so much more!

(so much more)

Each element could be isolated, then stored in glass jars—

Such tiny jars!—

And displayed on the mantel.

Meaningless.

As meaningless as that small lump of bronze

(elemental tin and copper)

Called the

Medal of Honor Given in reward

(supplication apology payment) for valor in action.

But Sn+Cu loses all value—

When the recipient is a small woman dressed in black,

Cradling a carefully folded flag.

Stream— September 11, 2001

Towers fall in on you on themselves

On the world

Crash

Burn and churn and break and

Kill and smoke and clouds and

Death and bits and—

Nuclear wrongness

Molecular weirdness

Broken broken smoke and soot and

Bits and pieces—

Hell begets hell begets

A baked land that, with parched mouth,

Calls— overflowing with maybes and where tos and how will I?

Mama please I’m hungry DaddyohDaddy

I’m so thirsty Mama—

Watching children die face down in the dust in pain

Bloated bellies, flies—

Ohdon’tleaveyourbabies

Nodon’teverleaveyourbabies

See the beatings the horror the war the rape

Get on a train for tomorrow

A hope a prayer for no more tears

And no more blood no more hungry

Mouths and pleading eyes

Overflowing with words and prayers and oh god have mercy on me

Cramped crowded squeezing hoping

Ohgodohgodohgodoh

Fragments of brain and bits of dreams and technology and the

Bright bright bright bright future—

“this is the way the world ends

this is the way the world ends

this is the way the world ends”

Not with a whimper but with screams and screams

And screams.

--Esme J. Sammons 2008

Positive Spin

Positive Spin